Weatherproof

Your World

Outsmart the weather to keep people safe and business productive.

Rapidly Respond to

Changing Weather

Baron Weather delivers the information you need so you can act fast and create the right response at the right place at the right time, regardless of the weather.

Smarter Solutions for Every Business, Government, and Community.

Data Integrations

Get the data you need down to the street level at a price you can afford. Our catalog houses hundreds of datasets to best meet your needs, with insights tailored for decision-makers.

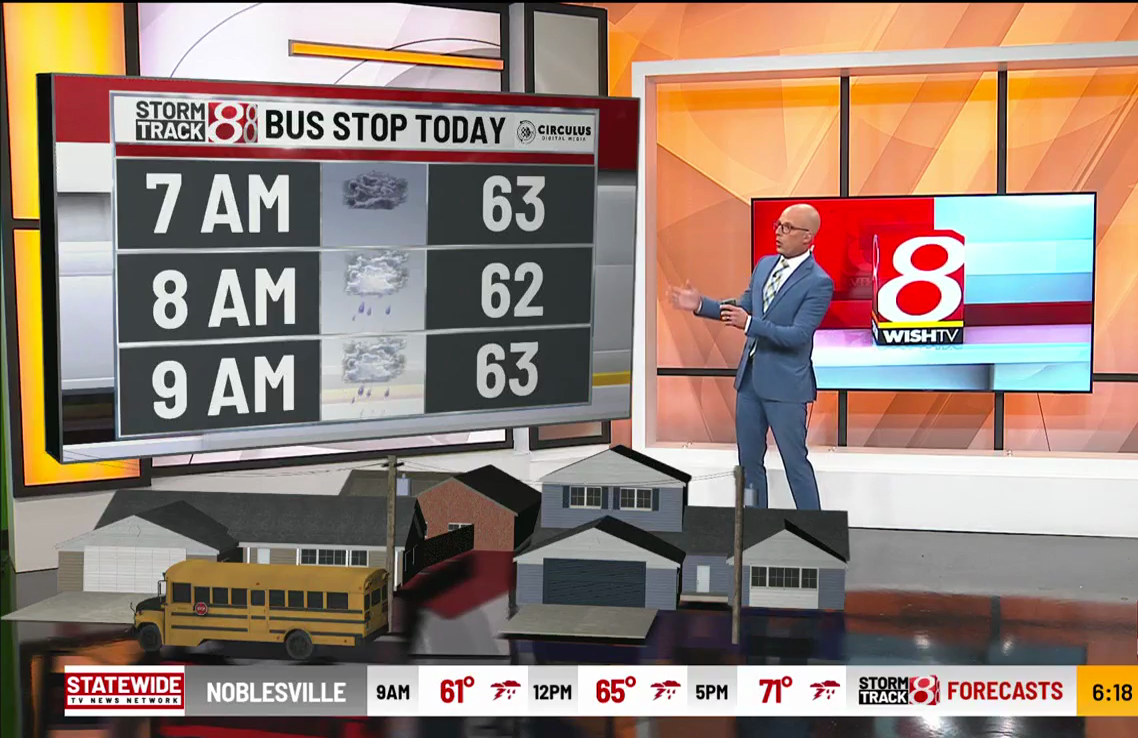

Software Applications

Unlock the power of a single system that provides all the data you need in one place, consolidated from multiple sources and topped off with exclusive Baron graphics.

Customizable Radars

Engineered for durability and sustainability, the Baron radar delivers high-quality data and minimizes long-term maintenance.

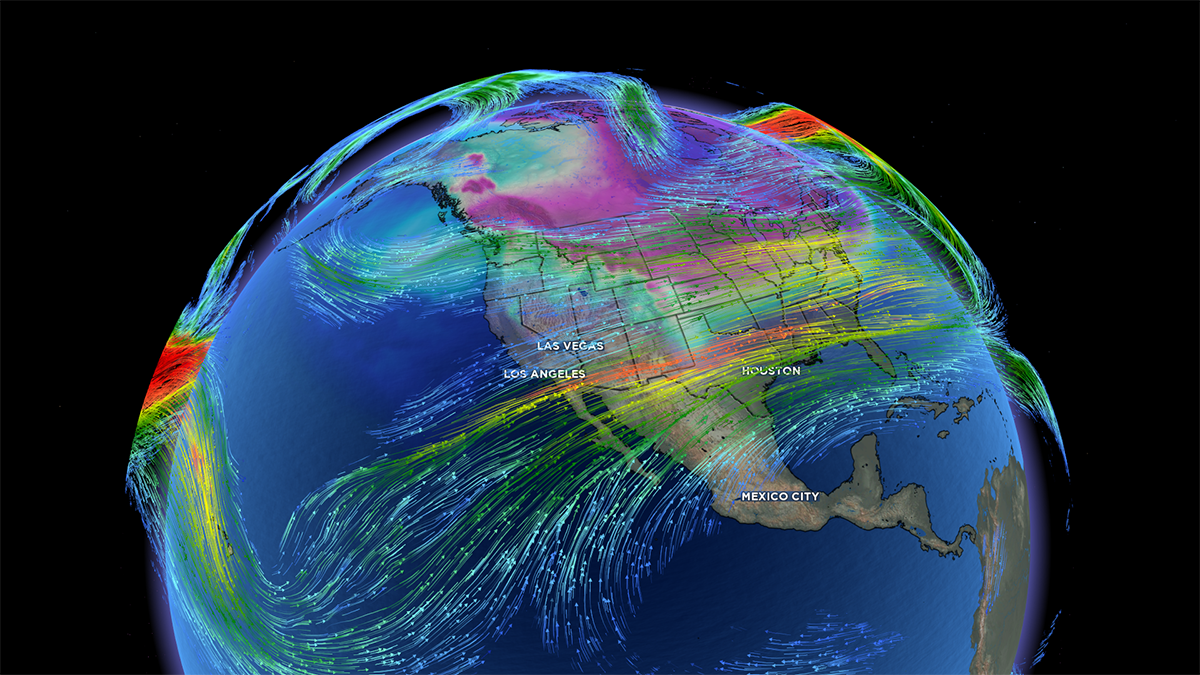

High-Res Modeling

Accurate off-the-shelf and configurable forecast models including atmospheric, hydrological, marine, air quality, and road surface coupled models.

Best-in-Class Datasets

User-Friendly Software

Precision Weather Radars

Exclusive Weather Modeling

Why Pay for a Weather Solution?

Baron surpasses free sources.

You can't control the weather, but you can steal its thunder.

When the weather starts acting up, free weather services and incomplete weather solutions often leave you with no choice: you over-prepare and waste resources or under-prepare and risk a dangerous outcome.

With Baron, there's a better option. A complete weather solution that provides the right information your organization needs at the right time so you can make better decisions.

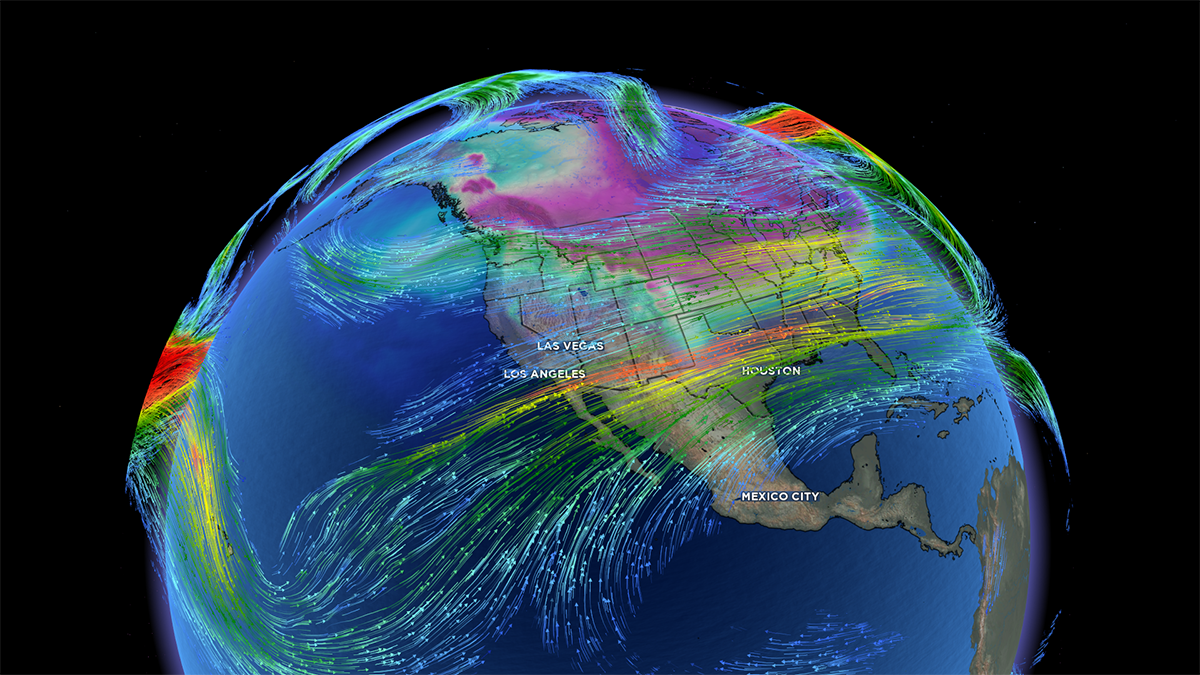

Hyperlocal Specificity

Weather information is often interpreted broadly, ignoring location-based variations. Typically, disaster strikes surgically, affecting one location very differently than another. This makes formulating an appropriate response difficult. Baron provides street-level granularity so you can craft the right response for your location.

Actionable Insights

You can't get the complete picture when relying on incomplete or free sources, which can leave you with more questions than answers. Baron delivers and synthesizes numerous data sources to deliver rich insights regardless of your expertise. Many of our solutions have built-in alerting and recommended actions to help guide your decision-making.

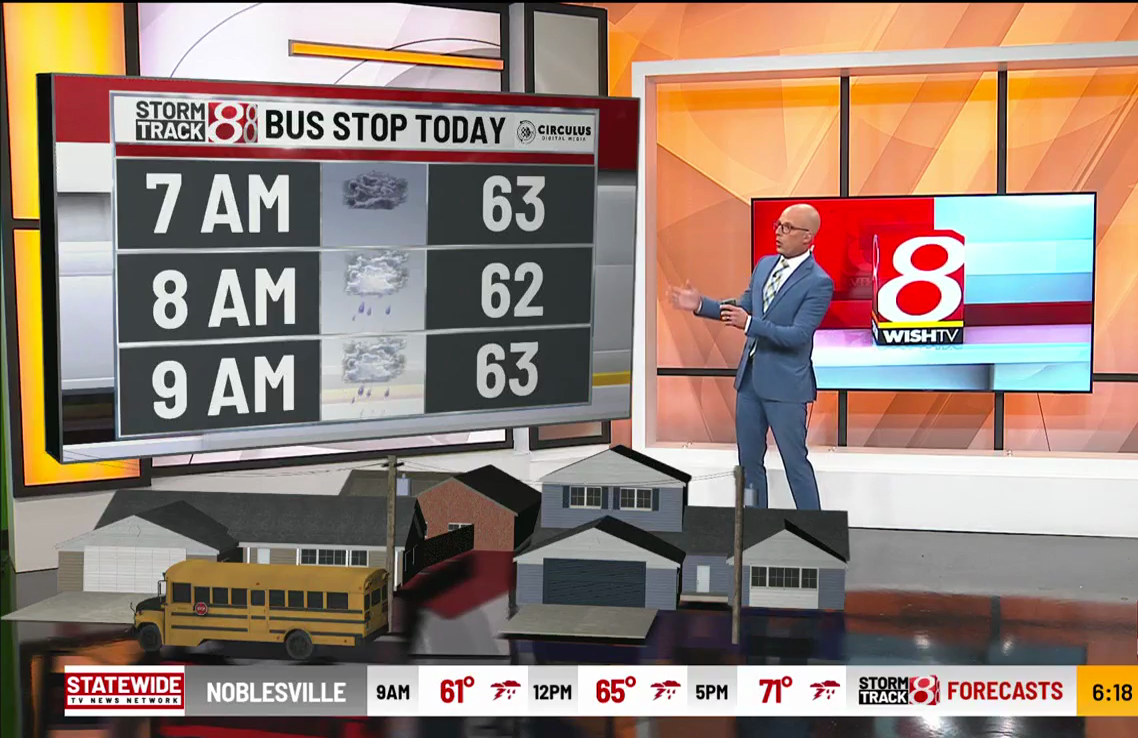

Share Info Easily and Quickly

Communication is key to crafting an effective response. If the weather data you’re working with is difficult and time-consuming to share, your response time can be slowed and not well received. Baron prepackages content that is shareable and easy to understand so that your response can be timely and effective.